Learning eBPF through gamification: The Hive CTF Challenge and Walkthrough

TL;DR: A (relatively) simple eBPF capture the flag challenge and writeup. The challenge was made by a colleague on the R&D team and the writeup by one of our detection engineers. The writeup goes through the whole discovery process and is a great way to dive into BPF.

Welcome to the Hive

A few weeks ago the R&D team at Red Canary created an internal CTF for anyone interested to participate in. The Hive (download here) is a challenge created by one of our staff engineers, Dave, who as far as I can tell does not want to be found on the Internet. The goal of the challenge was to introduce participants to the workings of BPF, in the hopes that the discovery/trial-and-error process of solving the challenge would give them a solid foundation in the technology. It turned out more successful than we hoped!

If you’d like to give the challenge a go, click that download link above and try to find the flag. You’ll need a relatively up to date Linux machine (we used Ubuntu 20.04, but it should work on a bunch of distros) with root credentials.

With that out of the way, below is a writeup by Del, one of our detection engineers. He did a great job documenting his path from knowing nothing about BPF to knowing something about BPF. If you get stuck, you can follow along below. Spoilers from here on out!

The Writeup

Keep scrolling.

Reverse Engineering thehive didn’t work out for me.

Using Ghidra to disassemble and decompile thehive was frustrating. It seems

that Rust, which is what thehive was written in, does not produce code that

Ghidra deals well with. This was further complicated by the fact the thehive

uses the Oxidebpf library, which

added another layer that needed to be understood. I had similar experiences

trying to use edb to debug the program while running. The only useful

information I extracted was to determine that the thehive doesn’t seem to pay

attention, to or collect, user input.

In retrospect, when you think about the nature of BPF, it makes sense that Ghidra and edb would only have visibility into the ‘loader’ program, and the guts of this challenge likely reside in the BPF program that it loads into the kernel.

Reverse Engineering the BPF program didn’t work out for me.

BPF programs run in a virtual machine hosted in the Linux kernel. They are loaded by a regular program which uses system calls that will verify and load the BPF program. BPF programs can read and write in memory data structures called ‘maps’. These ‘maps’ are the primary mechanism for a BPF program to communicate results to user space.

Although there are other interesting tools, it seems that two tools are most often mentioned as useful for investigating BPF programs: bpftool and bpftrace. The version of the kernel running has an impact on what information is available to these tools. BPF is an evolving capability and new capabilities are being added on a regular basis.

Roughly speaking, bpftool is a great tool for collecting data about, and manipulating, BPF programs after they’ve been loaded into the kernel. The bpftrace tool is great for loading and running BPF programs in a simple way from the command line (e.g. running one-line BPF programs).

Using bpftool, I was able to discover the BPF program that was being loaded by

thehive.

Running the command sudo bpftool prog list listed info about all the loaded

BPF programs, including:

57: kprobe tag a01e72fbd4579d51 gpl

loaded_at 2021-11-26T18:23:56-0700 uid 0

xlated 368B jited 203B memlock 4096B map_ids 1

pids thehive(2714)

One of the other capabilities of bpftool is to list a BPF program in the native

instruction set used by the BPF virtual-machine. Using this capability, once I

discovered the BPF program loaded by thehive, I was able to examine the code it

compiled to.

$ sudo bpftool prog dump xlated id 57

0: (85) call bpf_get_current_pid_tgid#135712

1: (63) *(u32 *)(r10 -4) = r0

2: (18) r1 = 0x5b5548405d585451

4: (7b) *(u64 *)(r10 -80) = r1

5: (b7) r1 = 0

6: (7b) *(u64 *)(r10 -24) = r1

7: (7b) *(u64 *)(r10 -32) = r1

8: (7b) *(u64 *)(r10 -40) = r1

9: (b7) r1 = 42

10: (7b) *(u64 *)(r10 -48) = r1

11: (18) r1 = 0x313b3d3736242010

13: (7b) *(u64 *)(r10 -56) = r1

14: (18) r1 = 0x2b25381424201734

16: (7b) *(u64 *)(r10 -64) = r1

17: (18) r1 = 0x2f1a222c2d333060

19: (7b) *(u64 *)(r10 -72) = r1

20: (b7) r1 = 102

21: (73) *(u8 *)(r10 -80) = r1

22: (b7) r1 = 1

23: (b7) r2 = 1

24: (bf) r3 = r10

25: (07) r3 += -80

26: (0f) r3 += r2

27: (71) r4 = *(u8 *)(r3 +0)

28: (bf) r5 = r1

29: (07) r5 += 55

30: (af) r4 ^= r5

31: (73) *(u8 *)(r3 +0) = r4

32: (07) r1 += 1

33: (07) r2 += 1

34: (15) if r2 == 0x40 goto pc+1

35: (05) goto pc-12

36: (bf) r2 = r10

37: (07) r2 += -4

38: (bf) r3 = r10

39: (07) r3 += -80

40: (18) r1 = map[id:1]

42: (b7) r4 = 0

43: (85) call htab_map_update_elem#160336

44: (b7) r0 = 0

45: (95) exit

I’ll spare you the details, but I spent a lot of time trying to reverse engineer this program. Basically: lines 0 - 23 load seemingly gibberish values into memory, lines 24 - 34 loop through those values in memory, XOR’ng each value with a different value. Finally, the rest of the program appears to load the resulting values into a map. It seems clear that the loop XOR’ng the values is decoding them, with the result then being loaded into a map.

Sadly, I was unable to decode the strings using this code. I’m sure it’s possible, but my binary foo wasn’t up to the job. Once I started asking myself if endianness mattered, and did I really understand how bytes were being stored by the vm, I threw up my hands and decided there had to be an easier way.

I did however, come to understand what this program does, and that it writes a value to a map. This value is almost certainly the flag!

Letting the BPF program do all the work did work out (eventually)

One of the capabilities of bpftool is the ability to dump the contents of a map.

Unfortunately, when I ran thehive, although it loaded the BPF program into the

kernel, it appears that the BPF program never runs. I say this because the

associated map never collects a value:

$ sudo bpftool map dump id 1

Found 0 elements

Looking at the data from bpftool prog list for the BPF program, we know that the

BPF program is attached to a specific kernel function via the kprobe capability

in BPF. This means that when that particular kernel function executes, the BPF

program attached to it will also be executed. So, it appears that when the

correct kernel function gets invoked, this BPF program will run (and write the

flag to the map associated with it).

So which system function is this BPF program attached to? There are literally thousands of possibilities:

$ sudo bpftrace -l | grep kprobe: | wc

51256 51256 1416114

(BTW, one of the complications with kprobes is that the set of kernel functions which are available, varies with the kernel. Since at this point I expected the BPF program to be attached to something that is often used (such as execve), I started to worry that maybe I was running a kernel that didn’t support the kprobe that thehive tried to attach the BPF program to. This led to building several VMs, each running the most current version of the kernel I could find. All to no avail.)

Luckily, I eventually discovered that one of the other capabilities of bpftool is to list any installed kprobes.

$ sudo bpftool perf list

pid 2714 fd 6: prog_id 57 kprobe func do_mount offset 0

Eureka! This reveals that the BPF has been assigned to the do_mount kernel

function. So, if I can arrange for that kernel function to be invoked, the BPF

program should execute and write the flag to the map. Even better, this

function sounds like it must be available everywhere.

Well, much hilarity ensued as I tried every way I could think of to use the

mount command to invoke the do_mount system call. The bottom line is that I

mounted ISO’s, devices, anything I could think of, all to no effect.

As a sanity check, I ran the following bpftrace program to monitor for do_mount

invocations:

$ sudo bpftrace -e 'kprobe:do_mount { printf("mount by %d\n", tid); }'

which confirmed that I was not successfully triggering the do_mount kernel

function.

Searching the list of kprobes (bpftrace -l) shows that do_mount is a legitimate

kprobe target, but I just wasn’t able to trigger it on several different kernels

that I tried. Researching do_mount didn’t provide a definitive answer, although

there was some suggestion that it’s only used during boot.

Author's note: what follows should not be necessary to get the solution. In our

own testing we were successful with running the standard mount command. The

command doesn't even need to succeed, so long as do_mount is invoked at some

point. But, honestly, Del's solution here is pretty darn clever.

So here I resorted to using a blunt instrument

Finally, in desperation, I decided to try patching the program to change which system function this BPF program was being associated with. A quick search using the strings program against the binary suggested that the name of the function was in fact being used to load the BPF program.

Using the ghex binary file editor I manually changed the instances of do_mount

to execve, since I knew that the execve kernel function was being invoked often.

I null terminated this string, since the do_mount strings appeared to be null

terminated (in Rust, strings aren’t necessarily null terminated). However the

patched binary panicked when I tried it.

On the theory that the strings were not null terminated, I searched the list of

kprobe names for one the same length as do_mount, and decided to try replacing

do_mount with do_rmdir.

With this change, the patched binary ran successfully. After starting my hacked verson of thehive as root, I executed the commands:

$ mkdir test

$ rmdir test

$ sudo bpftool prog list (to obtain the id of the map)

$ sudo bpftool map dump id 7

key:

ad 1a 00 00

value:

66 6c 61 67 7b 74 68 65 5f 70 72 6f 6f 66 5f 69

73 5f 69 6e 5f 74 68 65 5f 70 75 64 64 69 6e 67

7d 58 59 5a 5b 5c 5d 5e 5f 60 61 62 63 64 65 66

67 68 69 6a 6b 6c 6d 6e 6f 70 71 72 73 74 75 76

Found 1 element

Copying the hex strings above into CyberChef, and then running the ‘From Hex’ recipe with ‘Delimiter’ set to Auto, revealed the flag!

For me, this was a deep immersion in the modern BPF, something I had only fleetingly played with before. Overall it was a complete blast, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to play with it. I’d certainly appreciate any corrections or suggestions on better ways to approach this challenge.

Here are Some References:

- https://qmonnet.github.io/whirl-offload/2021/09/23/bpftool-features-thread/

- https://github.com/iovisor/bpftrace/blob/master/docs/reference_guide.md#bpftrace-reference-guide

- https://www.kernel.org/doc/Documentation/kprobes.txt

- https://ebpf.io/

- https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/linux-observability-with/9781492050193/

Here’s How to Reproduce the Solution

sed s/do_mount/do_rmdir/g thehive > thehive-hackedchmod 755 thehive-hackedsudo ./thehive-hacked- open another terminal tab, do the rest in that tab

mkdir testrmdir testsudo bpftool prog list- near end, find ‘kprobe’ with ‘loaded_at’ or ‘pids’ matching step 3, observe ‘map_ids’

sudo bpftool map dump id <id# from 'maps_ids' in step 8>- copy & paste ‘value:’ into a CyberChef window

- use the ‘From Hex’ recipe with ‘Delimiter’ set to Auto

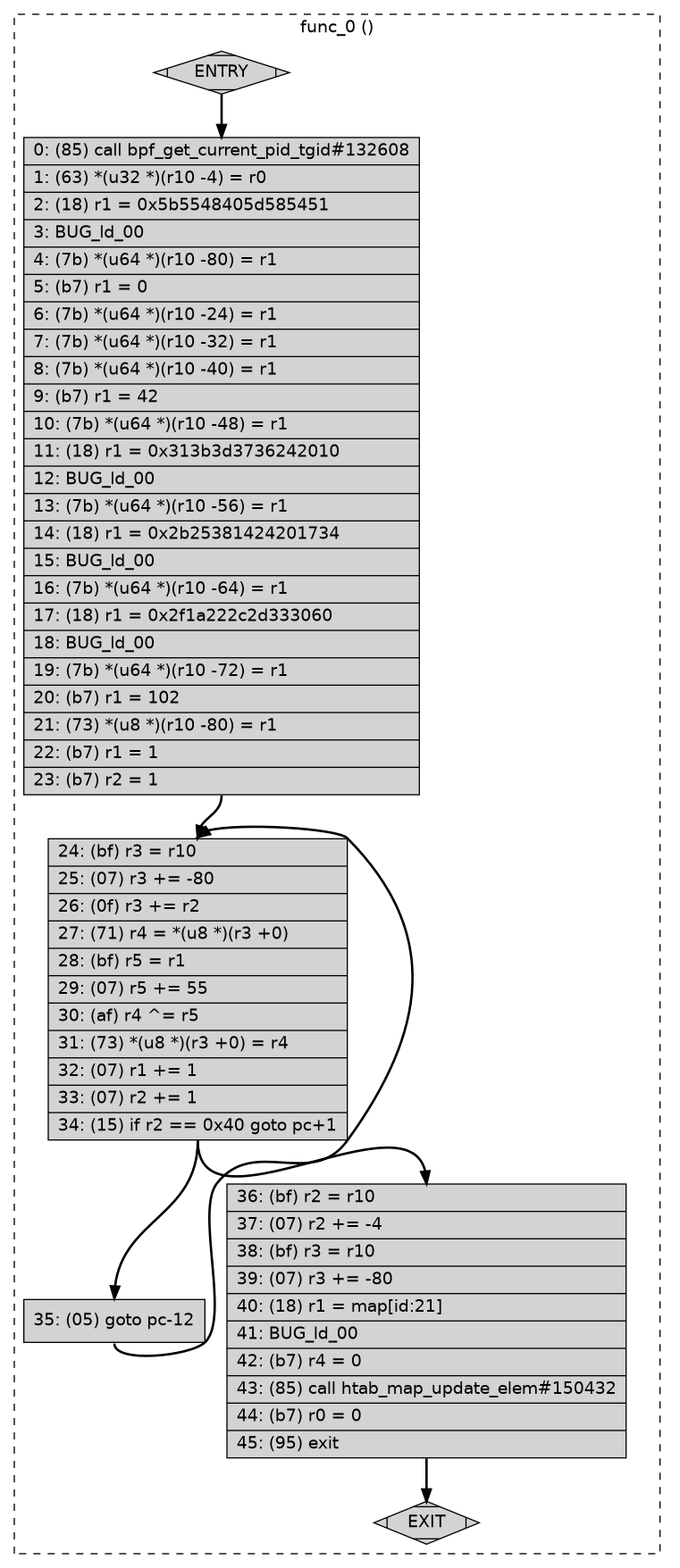

Control Flow Graph

Finally, in case it’s of interest, here’s a flow chart of the BPF program,

courtesy of bpftool prog dump xlated <id> visual: